What is Self-Sovereign Identity?

Self-Sovereign Identity represents the idea that a person should own and control their digital identities themselves instead of having to rely on an external party like SURFconext or Google to act as a broker for their digital identity. Users should also control when they wish to share personal data as well as which personal data they share with other parties. In such a system users authenticate themselves by presenting so-called claims to a service (also called a Verifier) to prove certain properties about themselves. Such a verifier might for example be webshop offering study material for students (like SURFspot).

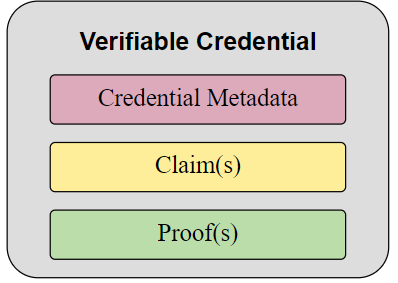

A claim, sometimes also called an attribute, is essentially a statement about the user. Examples of a claim/attribute are birth date, first name, second name or a student number. These claims are usually taken from a so-called credential. A credential is like a digital version of a physical ID card. Like their physical equivalents, these credentials contain a number of different claims about their subject. Credentials and the claims within them always have an authoritative source (called an Issuer), who is asserting these claims and issued this digital ID card to the user. This is usually a party that services recognise as a legitimate source for the specific type of credential and the claims within the credential. An issuer could for example be your university asserting that you are a student or professor at their institution.

Verifiers accept the claims presented to them because they trust the authoritative source(s) behind those claims. For this purpose users usually also present a digital proof to the verifiers to proof that the claims indeed come from trusted sources and have not been manipulated.

If you want to learn more about the technical characteristics, possibilities and challenges of SSI, I recommend reading SURF's Technical exploration on Ledger-based self-sovereign identity report.

Where does eduID come in?

Within an SSI environment, users use a so-called digital wallet, a piece of software, usually a smartphone app, to store their digital cards, i.e. credentials, akin to a physical wallet, where one usually carries around a bunch of different cards. However a digital wallet does much more than just store credentials. It also facilitates interaction with other parties (i.e. issuers and verifiers) and derives so-called presentations from the credentials within the wallet. These presentations contain a selection of claims (or even just one claim), that have been requested by a verifier in a way that only the requested claims need to be presented instead of having to present entire credentials, which also contain claims that the verifier does not need to know. This minimises the amount of data that users need to share and thus enhances their privacy.

The wallet is thus the component with which users interact with the wider SSI environment and is as such a very crucial part of an SSI ecosystem. This is where eduID comes in:

- eduID could become such a wallet in the form of an app.

- But eduID could also be an issuer that provides certain credentials such as a credential showing you are a student.

What open standards could be used in the implementation of an SSI system?

To implement such an SSI system, it is important to utilise open standards wherever possible. Two such standards that are used in most SSI systems are Verifiable Credentials (VCs) and Decentralised Identifiers (DIDs).

Verifiable Credentials define a standardised data model for credentials within an SSI system, which prescribes a certain structure. They include a proof, usually in the form of a digital signature to prove their validity. A wallet can then derive so-called verifiable presentations from these verifiable credentials, which only contain specific claims that have been requested.

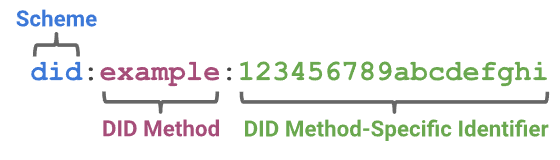

Decentralized Identifiers are a type of globally unique identifiers that are generated by their subject (like e.g. a user, an issuer or a verifier) themselves, of which they prove control via cryptographic proofs such as digital signatures.

Together with a so-called DID method, a DID is resolved to a DID document, which contains the actual data associated with the identifier, like a verification key and an endpoint.

DIDs can either be public, i.e. shared openly with other parties, or private/pairwise, where they are only shared with one other party. In eduID, users would ideally have a different private DID for each issuer and verifier they are interacting with to prevent tracking.

Additionally, protocols for the communication between the user and services (Issuers and Verifiers) are necessary and some do exist already. During my internship I examined two standards that are actually used in practice by some SSI systems, namely DIDComm, protocols that are based on relationships between parties that are based on their DIDs, and OpenID Connect Self-Issued OpenID Provider, an extension of the popular OpenID Connect protocol. However both standards currently suffer from a lack of widespread adoption and a lack of maturity (which to a lesser extends is also true for the data model standards).

What could this look like in practice?

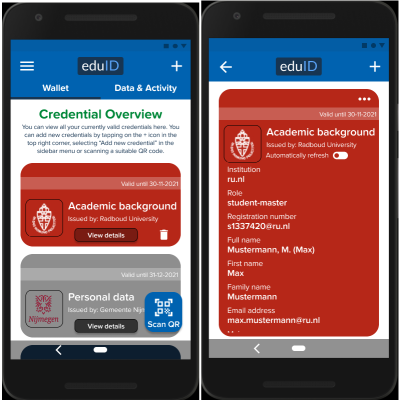

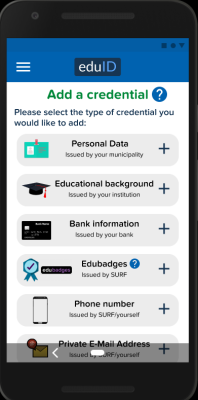

These illustrations demonstrate how an eduID wallet app could look like. Users see an overview of all credentials in their wallet, which they can also inspect in more details to see which claims they contain. To add a credential to their wallet, users usually scan a QR code.

In the prototype I build, it is also possible to add a credential by selecting them from a list. This should make it easier for users to get started since it makes it easy to fill the wallet with simple credentials from the get-go.

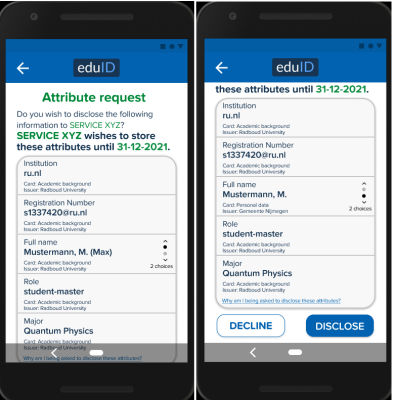

When a service (verifier) wants to know certain properties about the user or simply wants to authenticate them, they will usually display either a QR code, that the user needs to scan with their wallet app. The service will then display which properties they like to know about the user.

If the user is willing to share these claims, they can accept the request, otherwise they can just decline it.

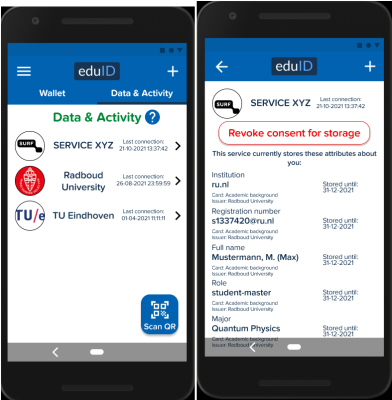

For eduID, this wallet app should also log past interactions in order to offer users some transparency, especially where some of their data is stored.

What would an eduID SSI ecosystem look like?

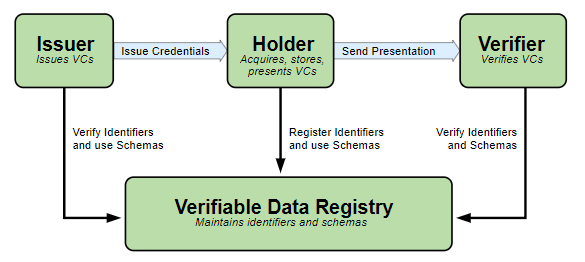

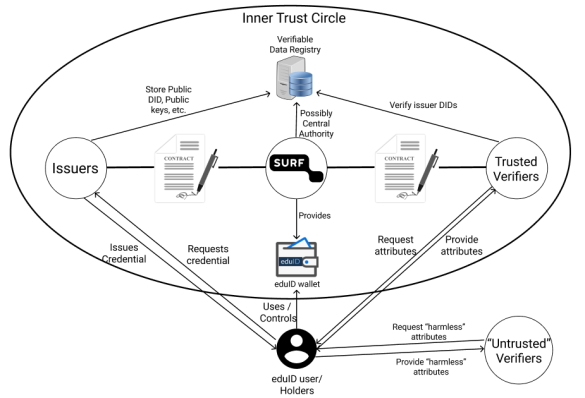

The illustration above shows the participants in a potential eduID SSI ecosystem and their interactions. In addition to the already listed participants, there is also the Verifiable Data Registry. The Verifiable Data Registry is used by participant to share data that is meant to be publicly accessible. In many existing SSI systems, this registry takes the form of a distributed ledger, i.e. a blockchain, but is also possible to use a central database or some other data structure for this.

A very important aspect in this system is the trust relationships between the different participants. It is very important that users and verifiers can trust issuers to issue a legitimate credential and that the issuer is a trusted source for the type of information contained in the credentials they provide to users. To establish this trust, issuers will most likely enter a contract with SURF to specify what kind of credentials they may issue and define their responsibilities. SURF as the provider of the eduID wallet would in this case be a trusted third party that vouches for these issuers.

Conversely, it is also important that users in particular can trust verifiers in the sense that:

- verifiers only request data they absolutely need

- verifiers treat privacy-sensitive data responsibly

Since the set of potential verifiers is quite large, not everyone can enter an individualised contract. One potential approach that the illustration models takes a hybrid approach with two categories of verifiers:

- trusted verifiers, who did sign a contract with SURF and may request privacy-sensitive data in specific contexts

- untrusted verifiers, who did not sign a contract and may thus only request non-privacy sensitive data

Conclusions

SSI offers a very interesting future for digital identity and eduID as it offers many advantages and opportunities to the actual users. However it is still a long way to get there due to the lack of maturity in many areas. In the future, there will probably be many SSI systems for different contexts and it will be important for these systems to be interoperable, i.e. that they are compatible with each other. For this purpose open standards need to mature and conventions on their implementation within the wider SSI community need to be established. SURF will closely follow the future developments of existing and new standards as well as conventions on the implementation of data models and protocols.

Want to know more?

If you have further questions or would like to learn more about my research you can read my full internship report or contact michiel.schok@surf.nl.

7 Praat mee