Marjon Baas

Onderwijskundige met specialisatie open & online en digitaal toetsen.… Meer over Marjon Baas

As Nicolai already stated in his blog yesterday, a lot of Open Educational Resources (OER) are out there but hidden in a jungle of repositories. Where Nicolai presented the findings of a study on the student perspective, this blog presents the findings of the teacher perspective. Finding OER is a main issue for teachers. So-called OER librarians could support teachers in finding OER by providing overviews of OER. Relevance however is determined by the teachers based on the OER characteristics, its perceived quality and the extent it fits the anticipated use (Cox & Trotter, 2017). In response to this, several organizations and institutes offer rubrics to scaffold teachers in this process. While these rubrics could be useful tools, most of them are not empirically tested (Yuan & Recker, 2015). More qualitative insights are needed on which elements teachers examine when assessing OER on quality.

‘Big’ OER

Two main categories of OER can be characterized: ‘big’ and ‘little’ OER (Weller, 2010). ‘Big’ OER are most often created by an institute, are often of high quality and are created for the purpose of learning, whereas ‘little’ OER are individually created without specific educational aims, are created with lower costs resulting in lower production quality. In this study, we focused on ‘big’ OER and although granularity might give an indication of quality, the assessment is a personal process undertaken by teachers. We therefore use the definition that quality resources are: ‘characterized by key characteristics which, from the teacher’s point of view, have an essential significance and determine whether the aid will be included in the teaching process.’ (Karolçík et al., 2017 p.315). The aim of our study, which is part of my PhD at ICLON-Leiden University, is to characterize the elements that teachers take into account when assessing OER quality and not to generalize what defines a quality OER. With this in mind, this study was conducted to explore how teachers assess ‘big’ OER on quality and to what extent their perceptions of OER changed due to collaborative dialogue about the quality of these OER.

Research design

In this study teachers got together to collaboratively assess a number of OER. Resources were discussed in subject groups (research methods, intercultural communication, business analytics), consisting of three or four teachers. Within each subject group, teachers answered three questions for each resource:

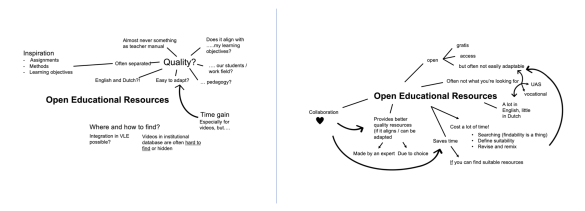

In addition to this, associations maps were collected before the plenary meeting (pre map) and three months thereafter (post map). Teachers were asked: ‘What do you associate with the term open educational resources? Write down everything that comes to mind, there are no wrong answers.’

The main findings are summarized below.

How do teachers assess ‘big’ OER on quality?

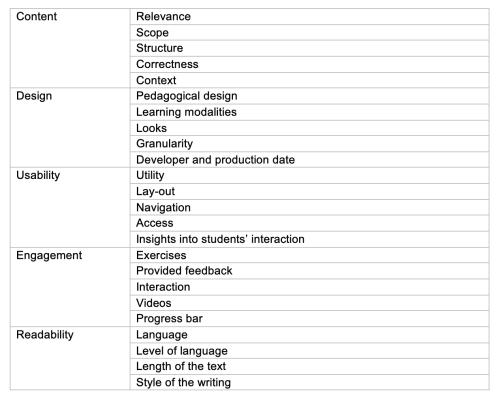

Five themes derived from teachers’ conversations that related to 1) content, 2) design, 3) usability, 4) engagement and 5) readability. The following elements were part of teachers’ conversations when discussion the OER.

If we compare these findings with the generic OER rubrics as presented by Yuan and Recker (2015), we see both similarities and differences.

Similarities relate to the assessment of content, the pedagogical design, the usability and engagement of a resource. The most remarkable difference is that while accessibility is mentioned in some rubrics, no remarks in our study related to accessibility. Although this could be due to the fact that teachers knew that all resources were open and that support on technical aspects was available. Another difference is the theme readability which is not explicitly mentioned in other rubrics except in Kurilovas et al. (2011). This could be explained by the context because all studies, except our study and that of Kurilovas, were set in an English-speaking country. Readability therefore appears to be subject of dispute for teachers in countries where English is not the native language of students.

To what extent did teachers’ perception of OER change?

Three main themes emerged from the comparison of the pre and post association maps. In the post maps it became clear that teachers had a richer understanding of OER and the implications of using OER. We identified the following three main themes:

In the image below you can see an example pre (left) and post map (right) of one teacher. In the pre map, primarily concerns on practical issues related to ‘where and how to find’ and ‘quality’ were noted. Does it fit with the objectives, the students and the context? Afterwards, the teacher was able to provide answers to the raised concerns regarding the availability, the fit for purpose, the required investment to revise and remix, and the language of the resources.

Practical implications

Based on the findings we suggest that:

References

Cox, G. J., & Trotter, H. (2017). An OER framework, heuristic and lens: Tools for understanding lecturers’ adoption of OER. Open Praxis, 9(2), 151–171. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.9.2.571

Karolčík, Š., Čipková, E., Veselský, M., Hrubišková, H., & Matulčíková, M. (2017). Quality parameterization of educational resources from the perspective of a teacher. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 313–331. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12358

Kurilovas, E., Bireniene, V., & Serikoviene, S. (2011). Methodology for Evaluating Quality and Reusability of Learning Objects. 9(1), 39-51.

Weller, M. (2010). Big and Little OER. In Open Ed 2010 Proceedings. Barcelona: UOC, OU, BYU. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10609/4851.

Yuan, M., & Recker, M. (2015). Not All Rubrics Are Equal: A Review of Rubrics for Evaluating the Quality of Open Educational Resources. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(5).

Onderwijskundige met specialisatie open & online en digitaal toetsen.… Meer over Marjon Baas

0 Praat mee